There is a dilemma at the heart of Joseph Smith’s first vision accounts. It is hidden in plain sight. Once you see it you wonder how you missed it before.

There is a new book out from an esteemed university press.*

One of its chapters illustrates how easy it is to miss the dilemma Joseph emphasized. The author compares Joseph’s experience to some early American conversion narratives and concludes that Joseph’s accounts lack the angst and the typical “transformations of the heart.”

“Nowhere in Smith’s first vision is there a description of the agonies and ecstasies of conversion,” this author claims. Joseph “presents himself not as one whose heart needs changing but one whose mind needs persuading.”

Notice the either/or: “not as one whose heart needs changing but one whose mind needs persuading.” This author thinks Joseph’s accounts are about resolving “cognitive dissonance” or intellectual incongruity “rather than ravishing a sinful heart with infinite love.” These phrases sound fancy but they are uninformed. This is a false dilemma posing as analysis.

This author has not heard what Joseph is saying

“Nowhere in Smith’s first vision is there a description of the agonies and ecstasies of conversion.” Really? Joseph’s accounts describe both his agony and his ecstasy. (More on that in later posts.)

I remember the day I finally saw the dilemma Joseph describes

It was lunch time. I was sitting outside. I had copies of all the first vision accounts and was reviewing them again, trying to look at them in new ways, asking different questions. I had read each of them many times before. But that day I started paying attention to the number of times Joseph described what was going on in his mind. Then I noticed that he distinguished between his mind and his heart. Then I saw it: Joseph’s was trying to tell me that his mind and his heart were at odds.

Every story has a problem

Every story has a problem

When Joseph told his story, the crux of the problem was that his soul depended on knowing how to act relative to Christ’s atonement–and how to act he did not know.

The Presbyterian option made sense in his head

He knew he was sinful. He also knew he hadn’t been able to do anything about it. That’s what the Presbyterian option taught him to expect. It made sense.

The Methodist option appealed to his heart

He attended Methodist meetings and witnessed sinful souls like his feel God’s redeeming love, and “he wanted to get Religion too wanted to feel & shout like the Rest but could feel nothing.” Methodism taught him to expect to feel God’s love if he gave himself to Christ. That didn’t happen, however. No matter how much his heart wanted Methodism, it seemed to his head like the Presbyterian explanation fit best.

One of the options appealed to his heart and the other to his head

No matter how much brain power he put into it, he did not know if his conclusions were right, and no matter how much he tried to follow his heart, he did not know if it was leading him right. That was the problem. His head was telling him one thing, his heart another. How could he know which was right? The welfare of his immortal soul was at stake. It was a terrible problem. These slices of Joseph’s Manuscript History Book A1, excerpted in the Pearl of Great Price as Joseph Smith-History, verses 10 and 18, highlight Joseph’s dilemma:

10 In the midst of this war of words and tumult of opinions, I often said to myself: What is to be done? Who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it? . . . .

18 My object in going to inquire of the Lord was to know which of all the sects was right, that I might know which to join. No sooner, therefore, did I get possession of myself, so as to be able to speak, than I asked the Personages who stood above me in the light, which of all the sects was right (for at this time it had never entered into my heart that all were wrong)—and which I should join.

Verse 10 is about Joseph’s thought process, about what’s gone on in his head. He has often wondered whether all the options are wrong and how he will be able to decide. The parenthetical clause in verse 18 is about Joseph’s emotional vulnerability. He tells us he has kept the awful, recurring thought that all the options for forgiveness are wrong from entering “into my heart.”

In 1902, church leaders tasked BH Roberts

with turning Joseph Smith’s history, originally serialized in 1842 in the Times and Seasons, into published volumes. While in that role, he had gathered the serialized “History of Joseph Smith” from back issues of the Millennial Star, the Saints’ British periodical, and bound it into three volumes that he kept and annotated.

His notes show that he thought Joseph contradicted himself in the passages quoted above

Joseph said he “asked the personages who stood above me in the light, which of all the sects was right, (for at this time it had never entered into my heart that all were wrong,) and which I should join.” Earlier, however, Joseph said that prior to his vision he had “often said to myself, what is to be done? Who of all these parties are right? Or are they all wrong together?”

The two lines seemed contradictory to Roberts

He knew that Joseph’s 1842 letter to John Wentworth said that at about age 14 he began to notice “a great clash” between churches and considered “that all could not be right, and that God could not be the author of so much confusion.” So Roberts silently elided the line for at this time it had never entered into my heart that all were wrong. That’s why those words are not in the published version of Joseph’s manuscript history (see top of page 6).

If BH Roberts couldn’t see

the dilemma Joseph tried to highlight, it seems wise to be humble and cautious about assuming that we have understood Joseph well. Working hard to listen to Joseph, using both brain and spirit, leads to seeing and hearing things in Joseph’s first vision accounts to which we may have been blind and deaf.

In my next post I’ll write about Joseph’s other dilemma

the one that kept him from telling his story, and that shaped the way he told it when he finally decided to do so. Stay tuned.

*Grant Shreve, “Nephite Secularization; or, Picking and Choosing in the Book of Mormon,” chapter 8 in Elizabeth Fenton and Jared Hickman, editors, Americanist Approaches to The Book of Mormon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 207-229. Quoted passages are from page 208.

Whiskey, whiskey, whiskey

Whiskey, whiskey, whiskey

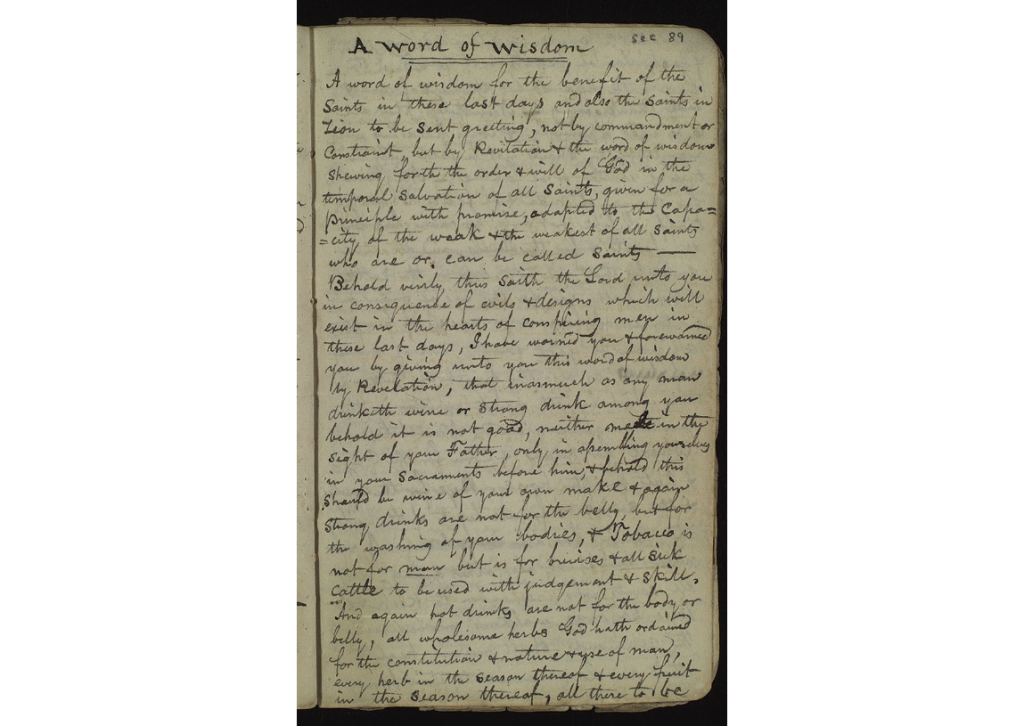

Joseph might find it odd but not unexpected that critics devour the evidence he left us that once in a while he had a beer or drank a glass of homemade wine or enjoyed sacramental wine, or that he was tempted by whiskey, or that he drank some while he was unjustly imprisoned in a depressing dungeon. He might be puzzled that some people have focused inordinate attention on prosecuting him while overlooking the prophetic Word of Wisdom he produced. “I never told you I was perfect,” Joseph said, “but there is no error in the revelations which I have taught.” It is not hard to find faults Joseph did not try to hide, but where are the flaws in his revelation known as the Word of Wisdom?

Joseph might find it odd but not unexpected that critics devour the evidence he left us that once in a while he had a beer or drank a glass of homemade wine or enjoyed sacramental wine, or that he was tempted by whiskey, or that he drank some while he was unjustly imprisoned in a depressing dungeon. He might be puzzled that some people have focused inordinate attention on prosecuting him while overlooking the prophetic Word of Wisdom he produced. “I never told you I was perfect,” Joseph said, “but there is no error in the revelations which I have taught.” It is not hard to find faults Joseph did not try to hide, but where are the flaws in his revelation known as the Word of Wisdom?