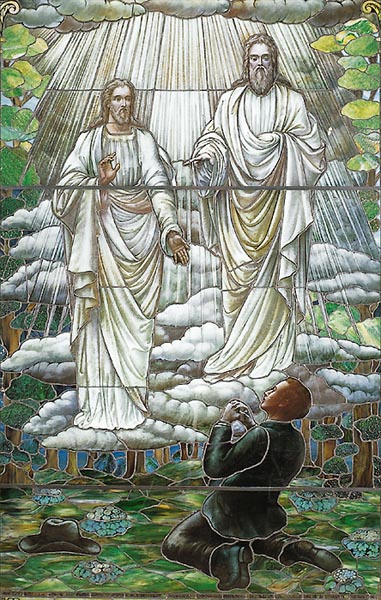

Did Joseph Smith see one divine being or two in his first vision? The question may seem absurd to Latter-day Saints who can quote the memorable line from the canonized account:

I saw two personages (whose brightness and glory defy all description) standing above me in the air. One of <them> spake unto me calling me by name and said (pointing to the other) “This is my beloved Son, Hear him”

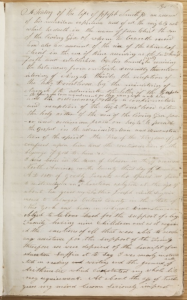

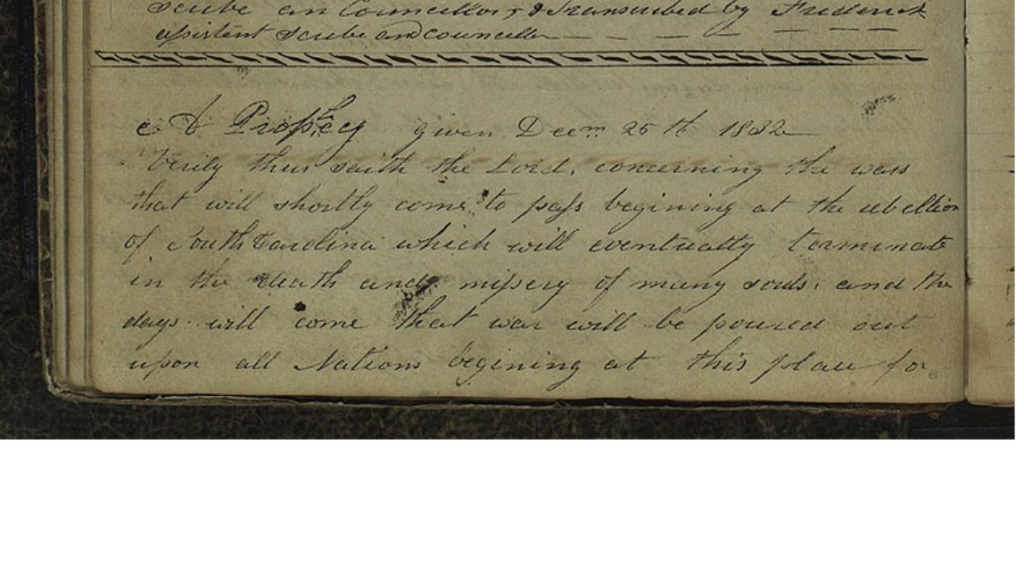

But seven years

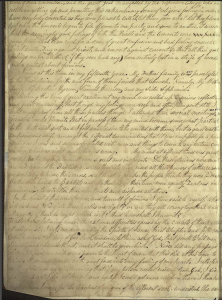

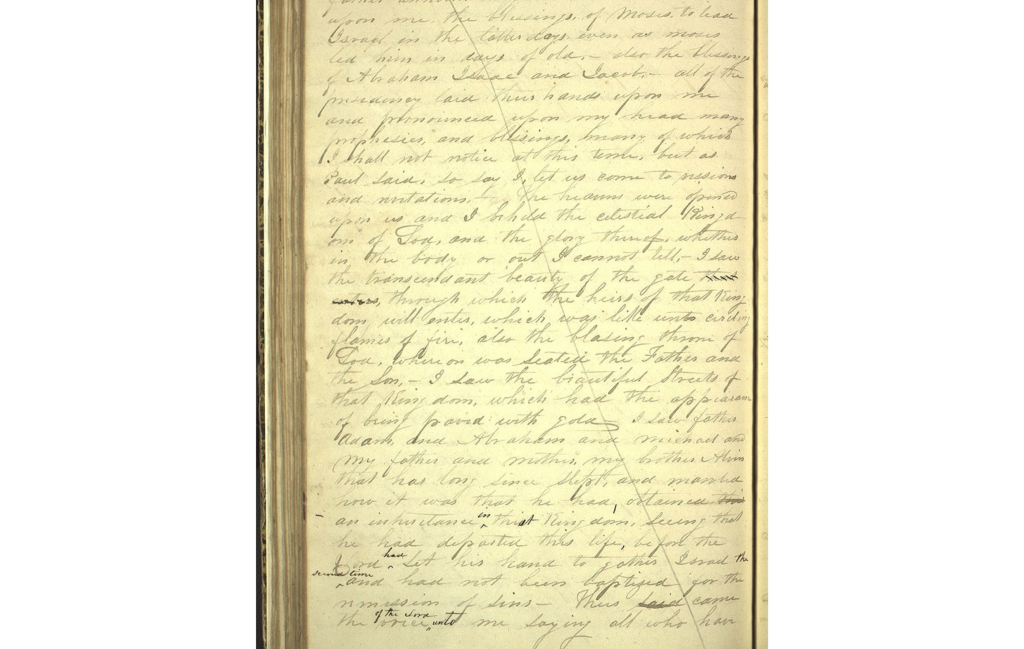

Before those words were written by his scribe, Joseph penned in his own hand, “the <Lord> opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord.” In this earliest known account of the vision, critics are quick to point out, Joseph describes the appearance of only 1 divine being.

Or does he?

Having studied all the available evidence carefully, I have concluded that what Joseph Smith struggled to communicate has not been understood by most critics or believers—and it won’t be until we learn to listen to him more carefully. On that point, see this earlier post.

When we listen to Joseph carefully

We hear him explain that he saw at least two divine beings in the woods but not necessarily simultaneously. In 1832 he wrote, “the <Lord> opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord.” His 1839 account says clearly, “I saw two personages” and the 1842 account adds, “two glorious personages.”

The distinction between

The 1832 account’s apparent reference to only one being—the Lord—and the 1839’s unequivocal assertion of two beings has led some to wonder and others to criticize Joseph for changing his story. But it may be that we just need to listen more carefully to Joseph tell the story. It may be that we have assumed that we understood his meaning before we did.

Joseph’s 1835 account provides the clearest chronology. He said,

a pillar of fire appeared above my head, it presently rested down upon me, and filled me with Joy unspeakable, a personage appeard in the midst of this pillar of flame which was spread all around, and yet nothing consumed, another personage soon appeard like unto the first, he said unto me thy sins are forgiven thee.

Two of the five secondary accounts also say that Joseph first saw one divine personage who then revealed the other. In an 1843 newspaper interview, Joseph reportedly said:

I saw a light, and then a glorious personage in the light, and then another personage, and the first personage said to the second, “Behold my beloved Son, hear him.”

In 1844, Joseph told Alexander Neibaur that he

saw a personage in the fire . . . after a w[h]ile a other person came to the side of the first

In the 1835 account Joseph also added as an afterthought, “and I saw many angels in this vision.”

There is nothing in the accounts

Requiring us to read these variations as exclusive of each other. In other words, there is no reason to suppose that when Joseph says, “I saw two personages,” he means that he saw them at exactly the same time for precisely the same length of time, or that he did not also see others besides the two. Moreover, because the 1835 account and two of the secondary statements assert that Joseph saw one being who then revealed the other, we can interpret the 1832 account to mean that Joseph saw one being who then revealed another, referring to both beings as “the Lord”: “the <Lord> opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord.”

We cannot be sure but it seems plausible that Joseph struggled in 1832 to know just what to call the divine personages. Notice that the first instance of the word Lord was inserted into the sentence after the original flow of words, as if Joseph did not know quite how to identify the Being. Or he may have written “I was filled with the spirit of god and he opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord,” and then tried to improve it by adding a t in front of he to make the, which would create the need to insert Lord after the fact (see below).

For original image, click here

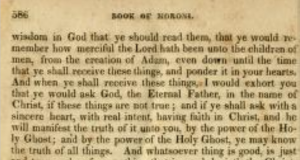

It’s also possible that Joseph purposefully evoked Psalm 110

In the King James Bible, Psalm 110 refers to two different divine beings both as Lord.

The Lord said unto my Lord, Sit thou at my right hand, until I make thine enemies thy footstool (Psalm 110:1)

Smarter people than me had that insight. John Welch and James Allen noticed it first and concluded “if David could use the word ‘Lord’ in Psalm 110:1 . . . to refer first to the Father and then to the Son (see Mark 12:36), so could Joseph” (Opening the Heavens, 2d ed., page 67 fn. 38). So could Jesus, and so could the writer of Acts, as Robert Boylan has shown.

In 1842

Joseph said that he “saw two glorious personages who exactly resembled each other in features, and likeness.” Of the nine accounts of his vision, four of them say he saw two personages, three say he saw one who then revealed another, and, as we have seen, the 1832 account may imply that. Only one of the nine, the Levi Richards journal entry, doesn’t specify. It says:

when he was a youth he began to think about these these things but could not find out which of all the sects were right— he went into the grove & enquired of the Lord which of all the sects were right— re received for answer that none of them were right, that they were all wrong, & that the Everlasting covena[n]t was broken

Next time someone declares that Joseph Smith said he only saw one divine being in 1832

Ask how they know. Only a few people who make that claim have actually studied the evidence. Everyone else is simply parroting what they’ve heard. They only know what they’ve heard. What if what they’ve heard is partial, meaning both incomplete and biased? Why rely on someone who hasn’t spent time with the evidence?

I have spent time with the evidence

And I don’t know whether Joseph meant in 1832 to refer to one divine being or two. However, in light of all the evidence it seems presumptuous to conclude that there is no other choice but that he must have only meant one. That’s a partial choice. The reason to choose it is to more conveniently be able to convict him of changing his story on cross examination.

So did Joseph Smith see one divine being or two in his first vision?

Well, seven times out of nine he said he saw two. Once the recorder didn’t capture enough of his account for us to know, and once he said “the <Lord> opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord.” You decide what he meant by that.

Tune in next time for a discussion of how old Joseph was at the time of his vision, or subscribe if you want to have a link sent to your inbox.

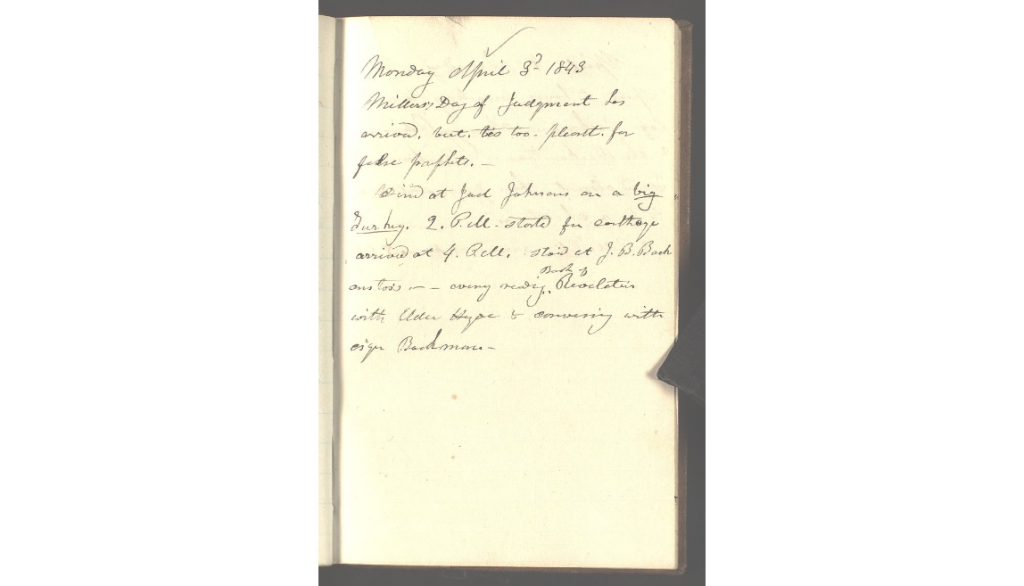

Whiskey, whiskey, whiskey

Whiskey, whiskey, whiskey

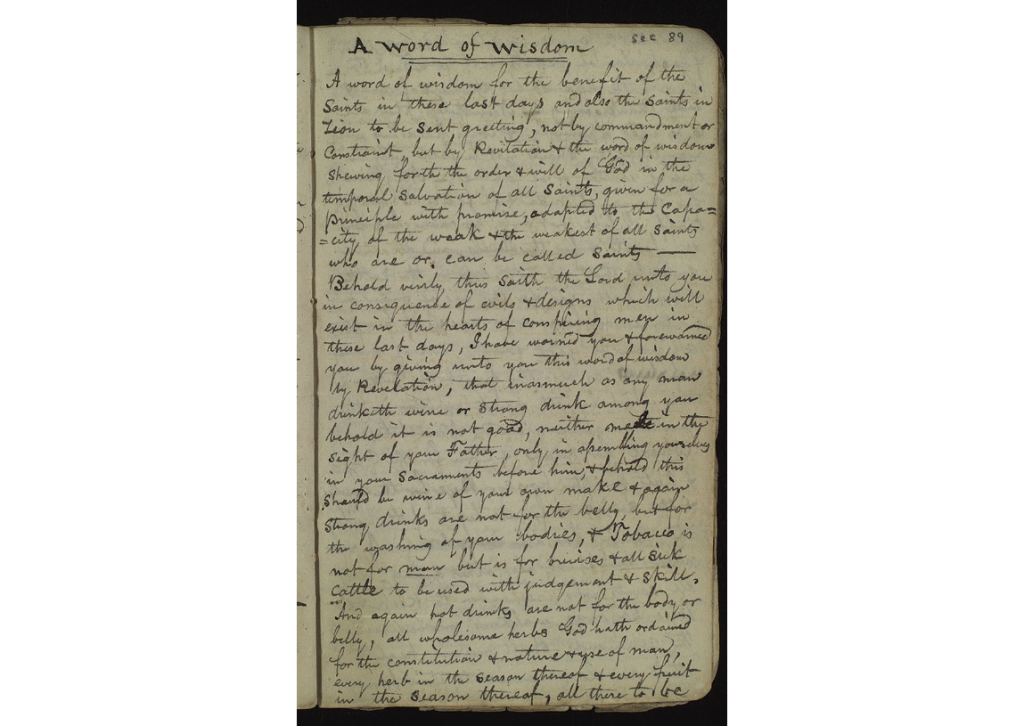

Joseph might find it odd but not unexpected that critics devour the evidence he left us that once in a while he had a beer or drank a glass of homemade wine or enjoyed sacramental wine, or that he was tempted by whiskey, or that he drank some while he was unjustly imprisoned in a depressing dungeon. He might be puzzled that some people have focused inordinate attention on prosecuting him while overlooking the prophetic Word of Wisdom he produced. “I never told you I was perfect,” Joseph said, “but there is no error in the revelations which I have taught.” It is not hard to find faults Joseph did not try to hide, but where are the flaws in his revelation known as the Word of Wisdom?

Joseph might find it odd but not unexpected that critics devour the evidence he left us that once in a while he had a beer or drank a glass of homemade wine or enjoyed sacramental wine, or that he was tempted by whiskey, or that he drank some while he was unjustly imprisoned in a depressing dungeon. He might be puzzled that some people have focused inordinate attention on prosecuting him while overlooking the prophetic Word of Wisdom he produced. “I never told you I was perfect,” Joseph said, “but there is no error in the revelations which I have taught.” It is not hard to find faults Joseph did not try to hide, but where are the flaws in his revelation known as the Word of Wisdom?