Section 137

Soteriology (so·te·ri·ol·o·gy) is theology about salvation. Christianity’s soteriological problem is based on three premises:

- God loves all people and desires their salvation (1 Timothy 2:3-4)

- Salvation comes to those who knowingly and willfully accept Jesus Christ as their Savior (John 3:16)

- Most people live and die without accepting Christ, or even knowing that they could or should

The problem says that all three premises are true but they can’t be reconciled. Proposed solutions tend to discredit one of the premises. Maybe God doesn’t desire the salvation of all people. Or maybe Jesus saves people who don’t knowingly and willfully accept Him.

The first Christians didn’t have this problem because they didn’t make the unstated assumption that makes it a problem in the first place. In other words, the first Christians didn’t believe that death was a deadline that determined a person’s salvation. Peter taught that Jesus Christ preached His gospel to the dead so they could be judged as justly as the living (1 Peter 3:18-20, 4:6). Paul taught that Christians could be baptized for the dead (1 Corinthians 15:29).

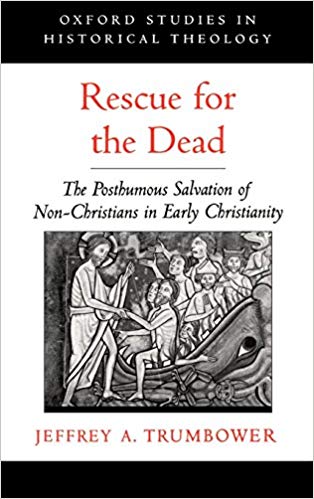

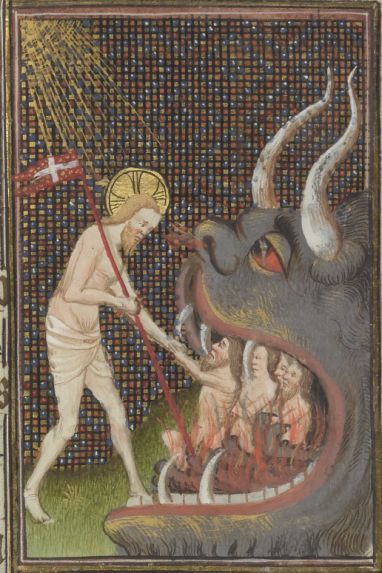

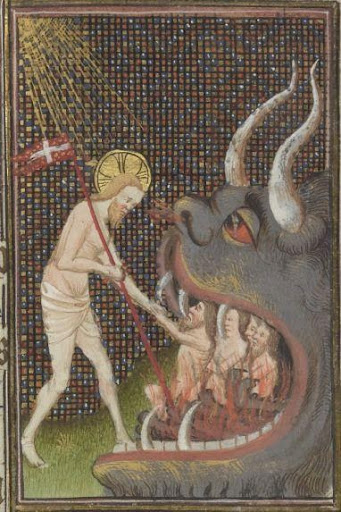

Jeffrey Trumbower’s very cool book Rescue for the Dead (Oxford 2001) traces the doctrine of redemption for the dead through Christian history. It turns out that it was Augustine, not Jesus or his apostles, who decided that death should be a deadline that determined a person’s salvation. But Augustine’s view prevailed in Christ’s church, at least in the West. Many medieval Christians continued to believe that (after his death and before his resurrection) Christ opened the spirit prison. They called this event the harrowing of Hell, and they created a lot of art depicting it.[1] My favorite images are the ones in which Hell is an awful monster, and Christ causes it to cough up its captive dead (as in 2 Nephi 9). However, the Protestant reformers, for all the good they did, generally followed Augustine on this point. Then along came Joseph Smith.

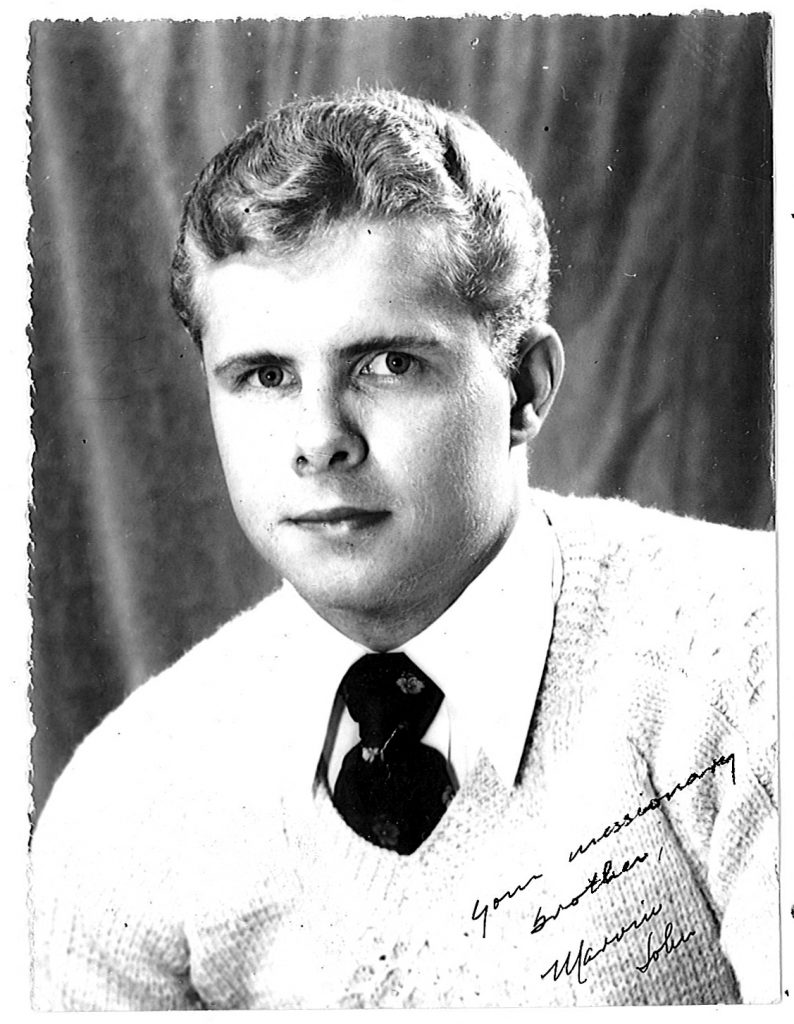

He was immersed in Protestant culture and assumptions. His big brother died painfully in 1823. The loss was heartbreaking to Joseph. It stung even worse when Reverend Benjamin Stockton implied pretty strongly at Alvin’s funeral that he would spend eternity in Hell. Joseph couldn’t reconcile Alvin’s goodness, Rev. Stockton’s doctrine, and a just and merciful God.

Fast forward twelve years to 1836. Joseph now knows from the Book of Mormon that unaccountable infants who die are not damned, but as distasteful as Rev. Stockton’s doctrine still sounds, Joseph doesn’t know that adults who die before embracing the Savior’s gospel are not automatically damned. Sincere and devout but mistaken theologians have caused this problem.

If you’re the Lord Jesus Christ, how will you solve it? How will you inform a world that has already decided otherwise that your saving grace reaches beyond death and saves all who choose to embrace your gospel? Joseph hasn’t even thought to ask. He is so thoroughly acculturated by Protestantism. So how do you get him to become open to it? How do you help him become aware of things he doesn’t know that he doesn’t know?

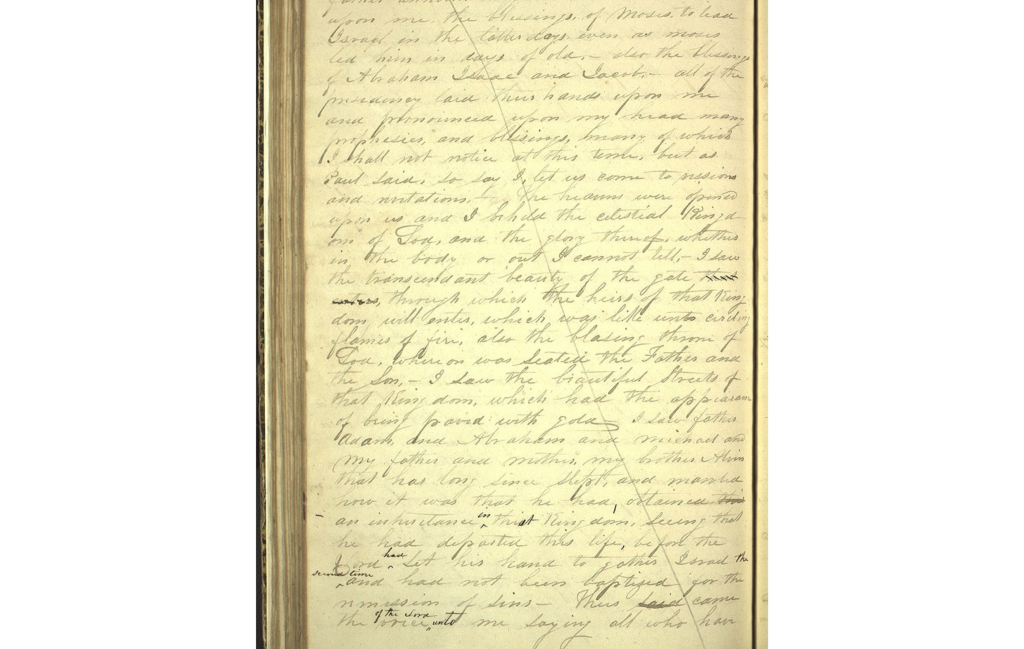

You show him a vision of the future, and of heaven, and you make sure he sees Alvin there. That makes him marvel and wonder. How will Alvin get past the flaming gates of God’s kingdom? Having purposely provoked the question, you answer it:

All who have died without a knowledge of this gospel, who would have received it, if they had been permitted to tarry, shall be heirs of the celestial kingdom of God— also all that shall die henceforth, without a knowledge of it, who would have received it, with all their hearts, shall be heirs of that kingdom, for I the Lord will judge all men according to their works according to the desires of their hearts (D&C 137).[2]

Desire, not death, is the determinant of salvation through Jesus Christ. He saves all who desire to be saved by Him once they know that good news. Which side of death they are on makes no difference. By removing the assumption that death determines salvation, Jesus resolved the soteriological problem for Joseph and for everyone else. There is no conflict between the premises now.

Section 138

Early Christians believed that people were not saved or damned based on when they lived or died, but based on what they decided to do with Christ’s offer of salvation when they learned about it. Over the subsequent centuries, however, death became “a firm boundary of salvation” in western Christianity.[1]

Based on teachings of Peter and Paul, medieval Christians continued to believe in what they called the “harrowing of hell,” Christ’s disembodied descent into the spirit world between his crucifixion and resurrection to redeem the captives. A rich tradition of drama and art depict the Savior’s mission of “deliverance” in which he declared “liberty to the captives who had been faithful” (D&C 136:18).[2]

A thousand years later, in 1918, the problem of death had not diminished and the aged Prophet Joseph F. Smith contemplated the same teachings of Peter and Paul. The Great War, known to us as World War I, was claiming more than nine million lives. A global influenza pandemic dwarfed that total. Worldwide the virus reaped a grim harvest of perhaps 50 million souls or more. It killed over 195,000 Americans in October 1918, the deadliest month in American history, the month the Lord revealed section 138.[3]

In the midst of the dead and dying was Joseph F., His father Hyrum had been brutally shot to death when Joseph was five. “I lost my mother, the sweetest soul that ever lived,” Joseph wrote, “when I was only a boy.”[4] His first child, Mercy Josephine, died at age two, leaving Joseph “vacant, lonely, desolate, deserted.” His eldest son died unexpectedly in January 1918, leaving President Smith “my overwhelming burden of grief.” In between those deaths, President Smith buried a wife and eleven other children.[5]

President Smith was ill as General Conference approached in October 1918. He surprised the Saints by attending on October 4 and speaking briefly. “I have dwelt in the spirit of prayer, of supplication, of faith and of determination; and I have had my communications with the Spirit of the Lord continuously.”[6] The day before, the Lord had given him the visions described in section 138.[7]

Section 138 is a Christ-centered testimony from beginning to end. It starts with President Smith pondering the Savior’s atonement, continues with a witness of Christ’s “harrowing of hell,” proceeds with the gospel of Jesus Christ being preached to departed spirits, and concludes in the name of Jesus. “I saw” (11), “I beheld” (15, 57), “I understood” (25), “I perceived” (29), “I observed” (55), “I bear record, and I know that this record is true,” Joseph F. declares (60).

He used powerful verbs to describe how he sought revelation. “I sat in my room pondering over the scriptures; And reflecting upon the great atoning sacrifice that was made by the Son of God, for the redemption of the world.” He intellectually “engaged” the soteriological problem of Christian theology and the most terrible questions of his time in which “the sheer, overwhelming quantity of death awakened individual and communal grief on an unprecedented scale. With the loss came questions: What is the fate of the dead? Do they continue to exist? Is there life after death?”[8] He returned to relevant Bible passages he already knew well and “pondered over these things which are written” (11).

That resulted in a series of visions. Joseph F. saw an innumerable gathering of the righteous dead, those who had been faithful Christians in life, “rejoicing together because the day of their deliverance was at hand” (15). They had been eager waiting for Christ to deliver them from the bondage of being disembodied, what verse 23 calls the “chains of hell” (cross reference D&C 45:17 and 93:33). The Savior arrived and preached the gospel to them but not to those who had rejected the warnings of prophets in life.

This vision led President Smith to wonder and inquire further. Christ’s miraculous three-year mortal ministry resulted in few converts. How could his short ministry among the dead be effective? What did Peter mean by writing that the Savior preached to the spirits in prison who had been disobedient? These questions brought another revelation, a recognition “that the Lord went not in person among the wicked and disobedient” but sent messengers. He mustered an army to wage war with death and hell. He “organized his forces” and armed them “with power and authority, and commissioned them to go forth and carry the light of the gospel to them that were in darkness, even to all the spirits of men; and thus was the gospel preached to the dead” (30).[9] Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and Wilford Woodruff all taught that the Savior unlocked the spirit prison and provided for redemption of the dead.[10] Not until Joseph F.’s vision, however, did mankind know how Christ “organized his forces,” “appointed messengers,” and “commissioned them to go forth” (D&C 138:30). That made it possible for the dead to act for themselves, to be fully developed free agents who were accountable for their new knowledge. The teaching fulfilled God’s just plan of salvation, making each individual responsible to receive or reject “the sacrifice of the Son of God” (35).

President Smith saw “our glorious Mother Eve, with many of her faithful daughters who had lived through the ages and worshiped the true and living God” (39). He must have moved to see his father, Hyrum Smith, together with his brother Joseph, “among the noble and great ones” (55). Most comforting to me is his vision of “the faithful elders of this dispensation, when they depart from mortal life, continue their labors in the preaching of the gospel of repentance and redemption, through the sacrifice of the Only Begotten Son of god, among those who are in darkness and under the bondage of sin in the great world of the spirits of the dead” (57). As both orphaned son and grieving father, President Smith appreciated the vision’s confirmation of “the redemption of the dead, and the sealing of the children to their parents” (48).

A survivor of the influenza pandemic repeatedly asked, “where are the dead?” Section 138 “answers this question and speaks to the great, worldwide need that underlies it.”[11] On October 31, 1918, ailing President Smith sent his son Joseph Fielding to read the revelation to a meeting of the First Presidency and quorum of the twelve apostles. They “accepted and endorsed the revelation as the word of the Lord.”[12] The Deseret Evening News published the revelation about a month later. In the meantime Joseph F. passed from life to death knowing better than anyone else what he could expect on arrival.

Section 137 notes

[1] David L. Paulsen, Roger D. Cook, Kendel J. Christensen, “The Harrowing of Hell: Salvation for the Dead in Early Christianity,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 19:1 (2010): 56-77.

[2] “Visions, 21 January 1836 [D&C 137],” p. 136-137, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 7, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/visions-21-january-1836-dc-137/1.

Section 138 notes

[1] Jeffrey A. Trumbower, Rescue for the Dead: The Posthumous Salvation of Non-Christians in Early Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 3-9, 126-40.

[2] K.M. Warren, “Harrowing of Hell,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume VII. (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910).

[3] George S. Tate, “The Great World of the Spirits of the Dead: Death, the Great War, and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic as Context for Doctrine and Covenants 138,” BYU Studies 46 no. 1 (2007): 27, 33.

[4] Joseph F. Smith, “Status of Children in the Resurrection,” in Messages of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, compiled by James R. Clark, 6 volumes (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965-75), 5:92.

[5] Joseph Fielding Smith, compiler, Life of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 476.

[6] Joseph F. Smith, 89th Semi-Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1918), 2.

[7] Joseph Fielding Smith, compiler, Life of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 466.

[8] George S. Tate, “The Great World of the Spirits of the Dead: Death, the Great War, and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic as Context for Doctrine and Covenants 138,” BYU Studies 46 no. 1 (2007): 21.

[9] The insight belongs to George S. Tate. See, “The Great World of the Spirits of the Dead: Death, the Great War, and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic as Context for Doctrine and Covenants 138,” BYU Studies 46 no. 1 (2007): 34.

[10] See Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 370. Brigham Young in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F.D. Richards, 1855-86), 4:285, March 15, 1857, and Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833-1898, Typescript., ed. Scott G. Kenney, 9 vols., (Midvale, Utah: Signature, 1983-84), 6:390.

[11] George S. Tate, “The Great World of the Spirits of the Dead: Death, the Great War, and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic as Context for Doctrine and Covenants 138,” BYU Studies 46 no. 1 (2007): 39-40.

[12] James E. Talmage, Journal, October 31, 1918, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University. Anthon H. Lund, Journal, October 31, 1918, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.