Section 125

From the confines of a jail cell in Liberty, Missouri, Joseph wrote to Bishop Partridge in Illinois that the saints could buy land in Iowa Territory for $2 per acre over twenty years with no money down, and the saints made a deal for the land.

Joseph escaped from Missouri and joined the saints in Illinois a few weeks later. He purchased land on a peninsula pushing into the Mississippi River across from the saints’ Iowa land, and named it Nauvoo. The Illinois land was comparatively expensive. Joseph hoped that the Church could buy it with consecrated funds and offer lots to the poor at prices they could afford, but the offerings were insufficient. It became clear that the Church would have to sell lots in order to pay its mortgage. So Joseph urged saints in outlying areas to gather to Nauvoo and help pay for the land. Saints across the river wondered if that applied to them. Joseph sought and received section 125 to answer their question.

The Lord’s will, declared in Section 125, is for the saints to build a city in Iowa across from Nauvoo, and to call it Zarahemla. The saints were to gather from everywhere else and settle there, in nearby Nashville, Iowa Territory; or across the river in Nauvoo. As usual, there is an explicit rationale in this revelation. The Lord gives a reason why the saints should do His will: “That they may be prepared for that which is in store for a time to come” (D&C 135:2).

Saints moved as a result of Section 125. It was read to the saints at General Conference on April 6, 1841. “Many of the brethren immediately made preparations for moving,” and came as soon as their planting was done.[1] Alanson Ripley reported that “Joseph said it was the will of the Lord the brethren in general . . . should move in and about the city Zerehemla with all convenient speed which the saints are willing to do because it is the will of the Lord.”[2]

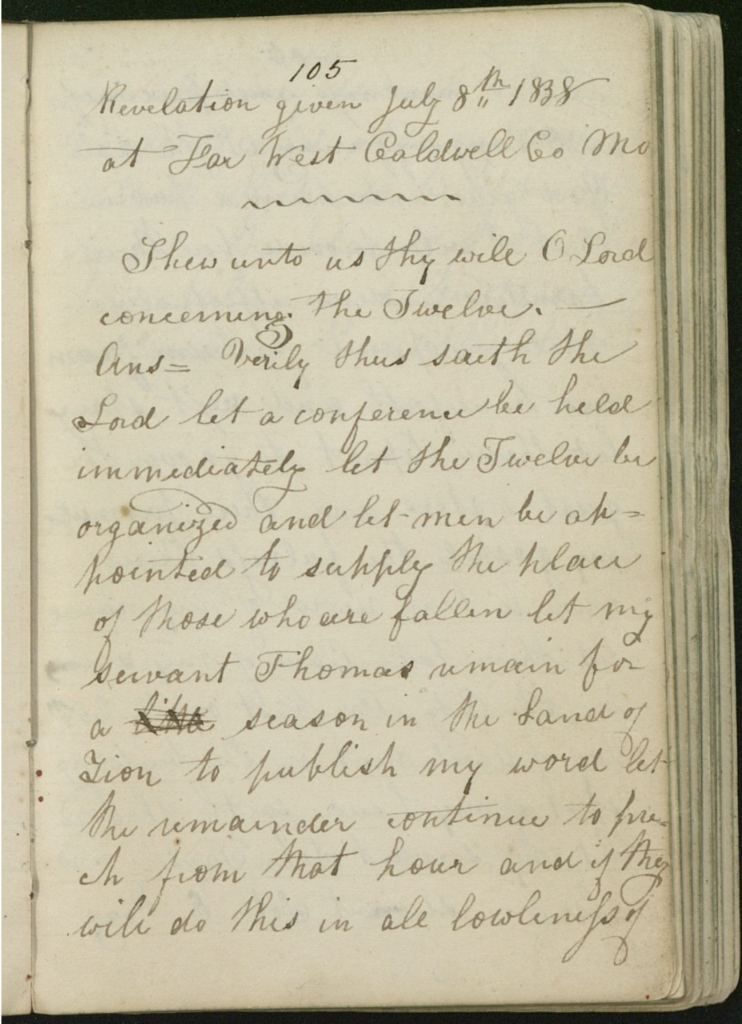

Section 126

Section 126 put Brigham Young in position to lead when Joseph’s mission was finished. Brigham answered the Lord’s call to serve in England (see section 118). Both he and his family were sick and homeless when Brigham left Nauvoo in the fall of 1839. While Brigham was in England, section 124 formalized his call as president of the quorum of the twelve apostles (D&C 124:127). Then, having converted hundreds, he returned to Nauvoo in July 1841 and found his family living in a small, unfinished cabin. A week later the Lord gave section 126 to Joseph.[1]

Joseph communicated the revelation to Brigham with his own affectionate introduction to his “Dear and well-beloved brother.” The Lord, having accepted Brigham’s offering in laborious missions away from home, no longer requires him to leave his family. Instead the Lord commands Brigham to send the Lord’s word abroad and look to the care of his family “henceforth and forever” (3).

Brigham set to work to care for his family. He chinked the cracks in the cabin, planted an orchard, built a cellar, and got up a garden to meet their needs. Joseph gave Brigham a few weeks and then assigned him to lead the apostles in taking care “of the business of the church in Nauvoo,” including overseeing missionary work (in obedience to section 126’s command to “send my word abroad”), the gathering of converts, and consecration.[2] This represented a shift in the apostles’ responsibility. Joseph had often kept them at arm’s length since their calling in 1835, testing them with tough assignments. Some of Brigham’s fellow apostles apostatized under that pressure. Brigham did everything the Lord asked of him. He had marched into hostile Missouri to obey a revelation. Then, sick and impoverished, he forsook everything else dear to preach the gospel in England.

As a result of section 126, Brigham remained near Joseph for the Prophet’s few remaining years, learning and receiving the temple ordinances and ultimately also the keys angels had conferred on Joseph.

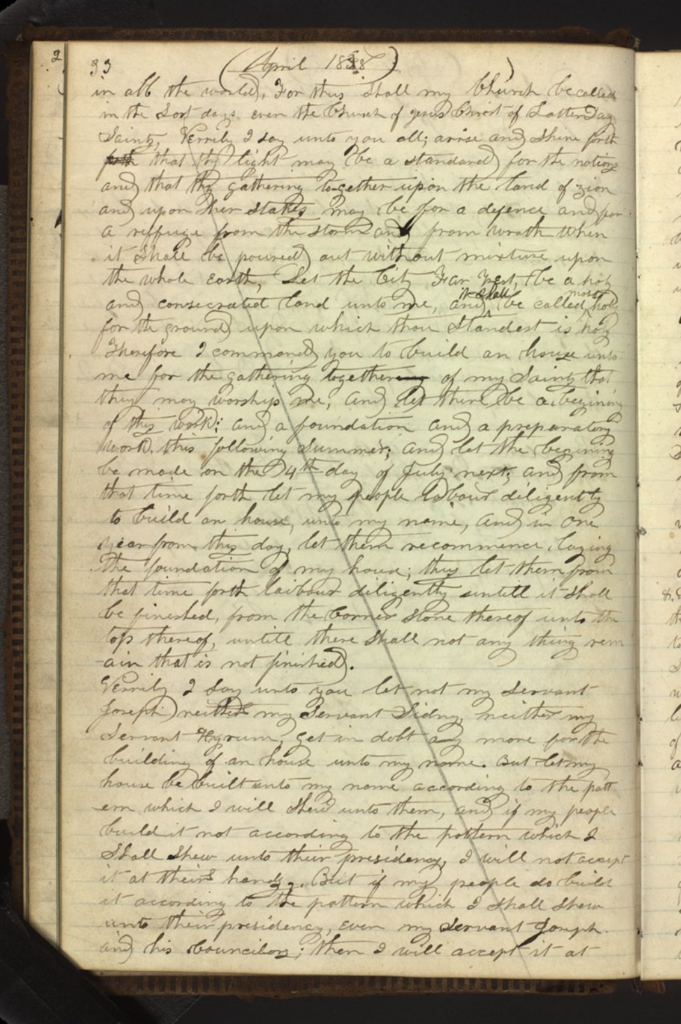

Section 127

In May 1838 in the Church’s Elders’ Journal, Joseph published questions he was frequently asked, including some provocative ones like: “Do Mormons baptize in the name of Jo Smith?”[1] In July he published the answers, including some snarky ones like, “No, but if they did, it would be as valid as the baptism administered by the sectarian priests.”[2]

Maybe the most important Q&A was this one: “If the Mormon doctrine is true what has become of all those who had died since the days of the apostles. Answer: All those who have not had an opportunity of hearing the gospel, and being administered to by an inspired man in the flesh, must have it hereafter, before they can finally be judged.”

Two years later, on a Nauvoo summer day in 1840, at the funeral of Seymour Brunson, Joseph Smith had more to say about that. He read most of 1 Corinthians 15, in which Paul refers to the early Christian practice of being baptized for the dead in anticipation of the resurrection “and remarked that the Gospel of Jesus Christ brought glad tidings of great joy.” Noticing Jane Neyman in the congregation, whose teenage son Cyrus had died without baptism, Joseph gave her the good news “that people could now act for their friends who had departed this life, and that the plan of salvation was calculated to save all who were willing to obey the requirements of the law of God.” It was “a very beautiful discourse.”[3]

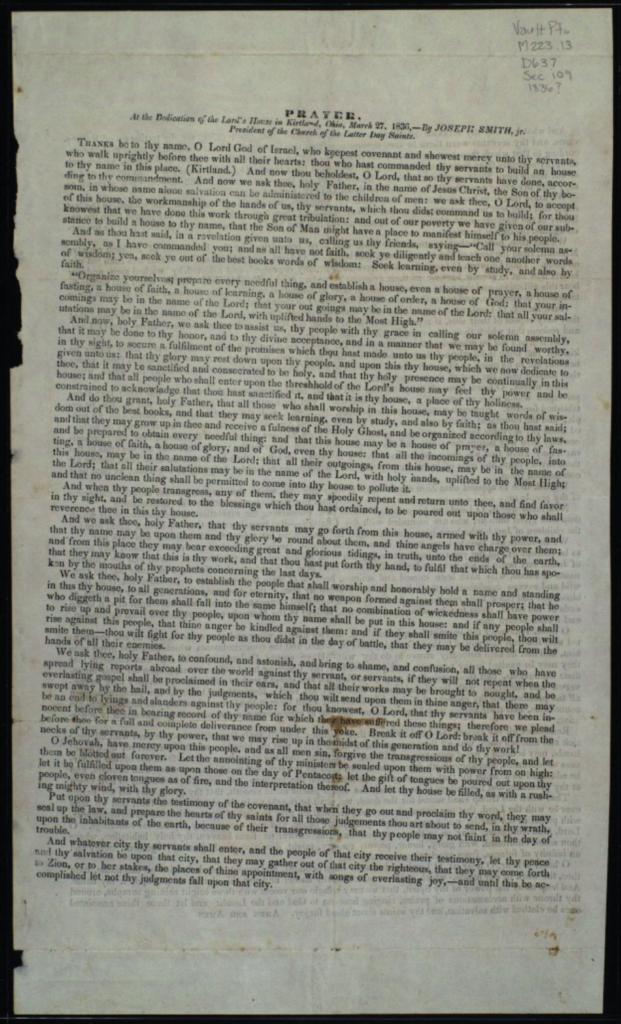

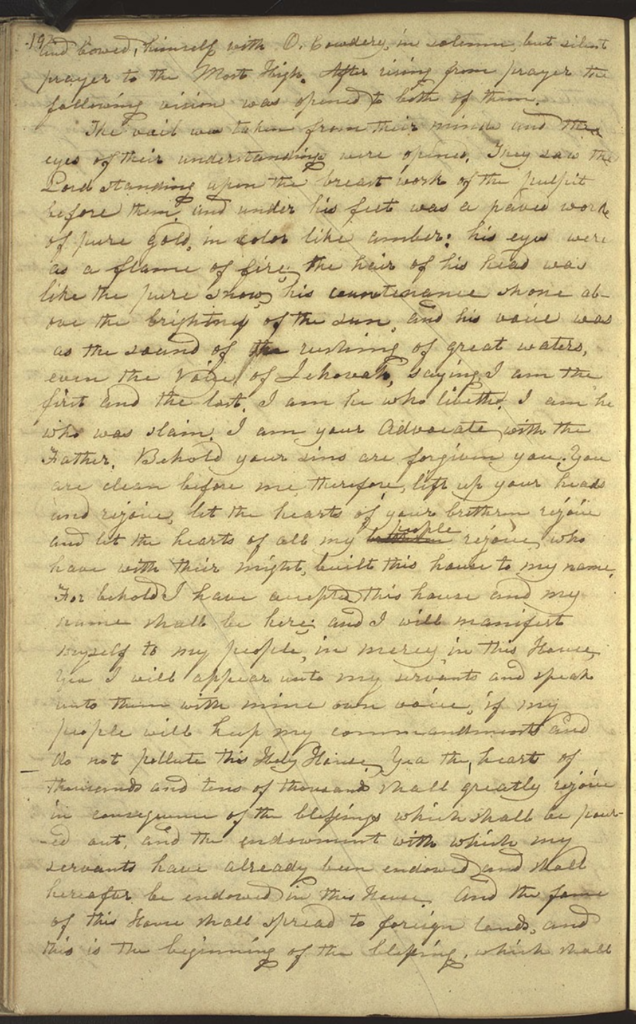

Joseph taught baptism for the dead again at October conference in 1840 as the saints eagerly performed the sacred ordinance in the Mississippi River in lieu of a temple baptismal font.[4] One witness wrote that “during the conference there were some times from eight to ten elders in the river at a time baptizing.”[5] But in their understandable zeal they were without knowledge. No one recorded the ordinances. A year later Joseph taught the doctrine in conference again and announced, as section 124 had declared in the meantime, that the Lord would no longer accept baptisms for the dead performed outside the temple (D&C 124:29-35).[6] The Saints thus pushed the temple toward completion, and just over a year later in November 1841 they performed the first baptisms for the dead in the unfinished but rising Nauvoo Temple.

In the midst of teaching the temple ordinances to the Saints, Joseph was charged with masterminding an attempted murder of former Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs. There was no evidence for the charge, and Joseph regarded it as another attempt by his enemies to get him to Missouri and lynch him. He hid instead of subjecting himself to that. Joseph was finally arrested in August 1842 but then released and the charges were finally dismissed a few months later.

Meanwhile, as Joseph moved from house to house in and around Nauvoo, protected by friends, he pondered the newly restored doctrines of the temple. There was something missing. He sought revelation while he was hiding and learned more about the nature of the ordinances. He looked for the first safe opportunity to teach the Saints. In August he taught the Relief Society that “all persons baptiz’d for the dead must have a Recorder present, that he may be an eye-witness to testify of it. It will be necessary in the grand Council, that these things be testified.”[7] The next day Joseph dictated a letter to the Saints, section 127, in which he shared some of what he had recently learned.

Joseph was nostalgic and melancholy as he hid from extradition officers bent on delivering him to a state in which there was no due process of law for Latter-day Saints. In section 127 he rehearses his eventful life, alternating between frustration at his enemies, the hostility that oppressed him, evidences of God’s deliverance, and hope for a final triumph. Mixed in are two revelations, the first in verse 4 and the second in verses 6-9, before Joseph closes with a lament that he is unable to teach the saints in person and a prayer for their salvation.

In the first revelation the Lord urges the Saints to finish the temple despite persecution. In the second He links recording the ordinances to their being sealed. That is, baptisms for the dead are not valid in heaven unless properly recorded by an eye-witness on earth. It is imperative that the saints learn the conditions on which ordinances performed on earth are validated in heaven, for, as the Lord declares in verses 8-9, he is about to restore more that pertains to the priesthood ordinances of the temple and the records of all such ordinances are to be in order and preserved in the temple.

Section 128

Baptism for the dead “seems to occupy my mind,” Joseph wrote. Less than a week after dictating section 127, Joseph dictated a much longer, more detailed explanation of the order of sacred ordinances: section 128. It adds practical instructions to 127’s revelation that baptisms for the dead, to be valid, must be recorded by an eye-witness. Joseph proposes a recorder for each of Nauvoo’s four wards, each of whom will account to a general church recorder who will be responsible to collect, certify, and keep the records.

Verse 5 uses three related words, order, ordinance, and ordained. Boyd K. Packer cited the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of order as “arrangement in sequence or proper relative position,” and noted how often the scriptures emphasize the importance of order. Ordinance, wrote President Packer, derives from order. He defined an ordinance as “the ceremony by which things are put in proper order.” Ordain, “a close relative of the other two words,” is the process of putting in order, including appropriately appointing someone to the ministry. “From all this dictionary work,” Elder Packer said, “there comes the impression that an ordinance, to be valid, must be done in proper order.”[2] That is precisely Joseph’s point in section 128. To be valid, an ordinance must be ordained of God, or, in other words, done according to the order or procedure he dictates.

Beginning in verse 6, Joseph traces the doctrine of recording earthly ordinances full circle through the Bible to make his point and substantiate what he had previously taught. He begins with the Biblical book of Revelation, in which John saw that the dead would be judged by what is recorded on earth, which is mirrored in the book of life kept in heaven (6-8). “It may seem to some to be a very bold doctrine that we talk of,” Joseph says, speaking of the priesthood’s power to seal earthly ordinances in heaven. But in defense he evokes Matthew 16’s description of Jesus’ promise to give Peter sealing keys to bind on earth and in heaven (9-10). Joseph then turns to the symbolic significance of baptism and cites Paul’s teaching at 1 Corinthians 15 and Hebrews 11:40. Joseph adds Malachi’s prophecy of the mission of Elijah to unite generations before the Savior’s second coming, and elaborates on its meaning.

With the teaching of temple ordinances, Joseph remarks that the dispensation of fulness “is now beginning to usher in, that a whole and complete and perfect union, and welding together” of generations, dispensations, and, indeed, of the human family can be accomplished (11-18). Joseph turns exultant at this prospect. Beginning at verse 19 he launches into a celebration of the restoration. Recounting the sources of his knowledge and priesthood power, Joseph lists a who’s-who of heavenly messengers he has seen—Moroni, Michael, Peter, James, John, Gabriel, Raphael, “all declaring their dispensation, their rights, their keys, their honors, their majesty and glory, and the power of their priesthood; giving line upon line, precept upon precept; here a little, and there a little; giving us consolation by holding forth that which is to come, confirming our hope” (D&C 128:19-22). At least one of the events to which Joseph refers—Michael teaching him how to detect false messengers (20)—must have taken place before Joseph moved from the Susquehanna River to Ohio in 1831, yet this is his first known mention of it. These verses are at least a partial answer to the questions when and by whom was Joseph endowed with priesthood power, becoming able to give the temple ordinances to the Saints?

In sum, Joseph had revelatory experiences and learned glorious truths that he did not readily share except in the right places at the right times to prepared people. That is exciting, and in a final burst of rhapsody, Joseph celebrated the profundity of the revealed solution to the terrible theological problem that has perplexed every thoughtful Christian: “What about those who never heard?”[3] The answer? “The King Immanuel . . . ordained, before the world was, that which would enable us to redeem them out of their prison; for the prisoners shall go free” (D&C 128:22).

Joseph had spent the winter of 1838-39 in a cold, tiny cell in Liberty, Missouri, and when he dictated section 128 he was hiding from unlawful extradition efforts to get him back to Missouri. He had some sense of how it felt to be liberated from prison. Joseph closed section 128 excited about these “glad tidings of great joy” (19) and tells the Saints what to do with them. It’s the same thing the Lord’s current prophets and apostles are urging us to do: “Let us, therefore, as a church and a people, and as Latter-day Saints, offer unto the Lord an offering in righteousness; and let us present in his holy temple, when it is finished, a book” or, more recently, electronic files or cards “containing the records of our dead, which shall be worthy of all acceptation” (23). In other words, let us organize families in the order God ordained. Let’s take disordered families and put them in order via the performance of holy ordinances in the House of the Lord.

Having shown that baptism for the dead was practiced by the earliest Christians but not since, Professor Hugh Nibley asked, “where did Joseph Smith get his knowledge? Few if any of the sources cited in this discussion were available to him; the best of these have been discovered only in recent years, while the citations from the others are only to be found scattered at wide intervals through works so voluminous that even had they been available to the Prophet, he would, lacking modern aids, have had to spend a lifetime running them down. And even had he found such passages, how could they have meant more to him than they did to the most celebrated divines of a thousand years, who could make nothing of them? This is a region in which great theologians are lost and bemused; to have established a rational and satisfying doctrine and practice on grounds so dubious is indeed a tremendous achievement.”[4]

It is impossible to estimate the results of these revelations, these glad tidings. Because of them innumerable spirit prisoners have gone free. “Shall we not go on in so great a cause?” (D&C 128:22).

Section 125 notes

[1] George D. Smith, editor, An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton (Salt Lake City: Signature, 1995), 86.

[2] Alanson Ripley, in John Smith, Journal, 6 March 1841, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Section 126 notes

[1] “Revelation, 9 July 1841 [D&C 126],” p. 26, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 5, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revelation-9july-1841-dc-126/1. Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Knopf, 1985), 98.

[2] Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Knopf, 1985), 99-100.

Section 127 notes

[1] “Questions and Answers, 8 May 1838,” p. 43, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 7, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/questions-and-answers-8-may-1838/2.

[2] “Elders’ Journal, July 1838,” p. 43, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 7, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/elders-journal-july-1838/11.

[3] Simon Baker, in Journal History of the Church, August 15, 1840, CHL.

[4] John Smith, Journal, October 15, 1840, CHL.

[5] Vilate Kimball to Heber C. Kimball, October 11, 1840, CHL.

[6] Minutes of the General Conference of the Church Held at Nauvoo, Elias Smith and Gustavus Hills, Rough Draft Notes of History of the Church, 1841, 17, CHL. History of the Church, 4:423-429.

[7] Joseph Smith, Discourse, August 31, 1842, Nauvoo Illinois, “A Record of the Organization and Proceedings of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo,” 80-83, CHL, in Andrew Ehat and Lyndon Cook, editors, Words of Joseph Smith, 129-31.

Section 128 notes

[1] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, September 19,1842, CHL.

[2] Boyd K. Packer, The Holy Temple (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 144-45.

[3] John Sanders, editor, What About Those Who Never Heard?: Three Views on the Destiny of the Unevangelized (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1995).

[4] Hugh Nibley, “Baptism for the Dead in Ancient Times,” Mormonism and Early Christianity, 148-49.